|

|

Tuvalu---the touchstone of global warming and rising sea level

Cliff Ollier

[First published in Online Opinion on 26 November 2010]

Introduction

I taught an introductory course in Geology at the University of the South Pacific in 1977. Each of the countries that participated in USP was invited to send 2 students. They had varying interests, and it was amusing to watch how they woke up when we were teaching geology relating to their own job. Some were interested in gold mining, others in highways and landslides, some in coastal erosion, others in active volcanoes. It was rather a surprise when the sole student from Tuvalu approached me one day and said "Sir, this is all wasted on me. My island is just made of sand." Any news from Tuvalu always struck a chord from that moment.

Since then, of course, Tuvalu has become "hot news" as the favourite island to be doomed by sea level rise driven by global warming, allegedly caused in turn by anthropogenic carbon dioxide. If you look up Tuvalu on the internet you are inundated with articles about its impending fate. Tuvalu has become the touchstone for alarm about global warming and rising sea level.

The geological background

There may have been good reason to think that Tuvalu was doomed anyway. Charles Darwin, who was a geologist before he became a biologist, gave us the Darwin theory of coral islands which has been largely substantiated since his time. The idea is this: When a new volcano erupts above sea level in the tropical ocean, corals eventually colonise the shore. They can grow upwards and outwards (away from the volcanic island) but they can't grow above sea level. The coral first forms a fringing reef, in contact with the island. As it grows outwards a lagoon forms between the island and the living reef, which is then a barrier reef. If the original volcano sinks beneath the waves a ring of coral betrays its location as an atoll.

But besides the slow sinking of the volcanic base there are variations of sea level due to many causes such as tectonics (Earth movements) and climate change. If sea level rises the coral has to grow up to the higher sea level. Many reefs have managed this to a remarkable extent. Drilling on the coral islands Bikini and Eniwetok shows about 1500m thickness of limestone and therefore of subsidence. Coral cannot start growing on a deep basement, because it needs sunlight and normally grows down to only 50 m.

If the island is sinking slowly (or relative sea level rising slowly) the growth of coral can keep up with it. In the right circumstances some corals can grow over 2 cm in a year, but growth rate depends on many factors.

Sometimes the relative subsidence is too great for the coral to keep pace. Hundreds of flat-topped sea mountains called guyots, some capped by coral, lie at various depths below sea level. They indicate places where relative sea level rise was too fast for coral growth to keep pace.

Sea level and coral islands in the last twenty years

What about the present day situation? The alarmist view that Tuvalu is drowning has been forced upon us for twenty years, but the island is still there. What about the changes in sea level?

Rather than accept my interpretation, look at the data for yourself. First take a regional view. For a number of well-studied islands it can be located at:

http://www.bom.gov.au/pacificsealevel/picreports.shtml

The Tuvalu data is provided at:

http://www.bom.gov.au/ntc/IDO60033/IDO60033.2009.pdf.

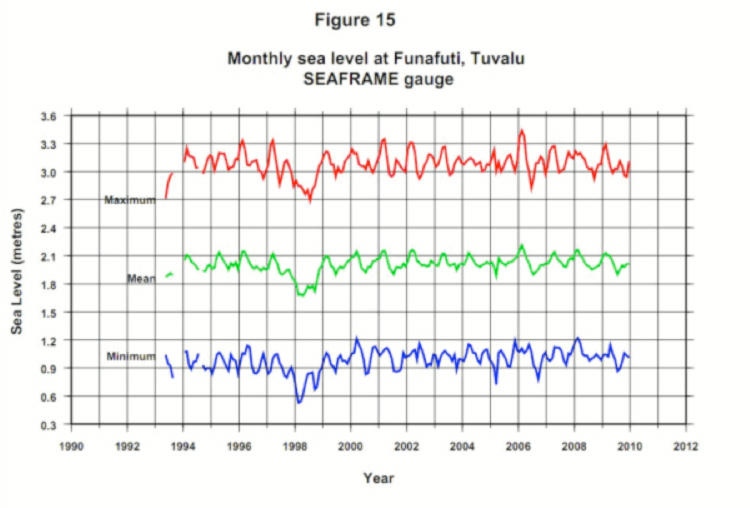

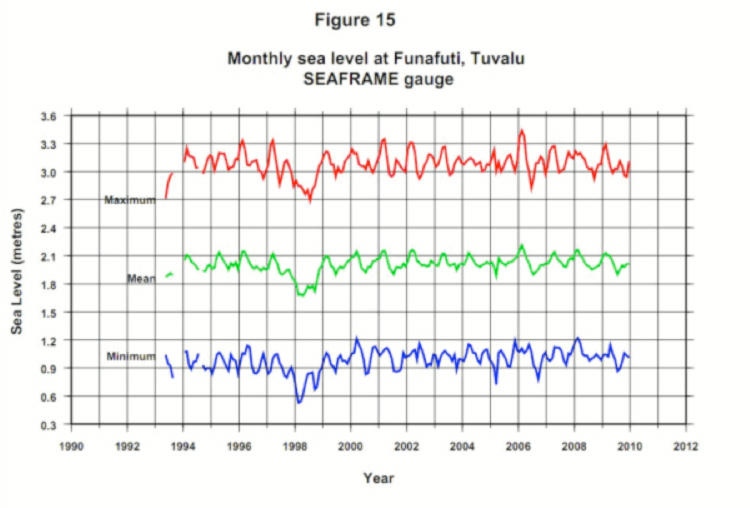

The results are shown graphically in their Figure 15 and reproduced here.

These island data have never been published in a "peer reviewed" journal. They are only available on the Australian Bureau of Meteorology website in a series of Monthly Reports, as in the examples given above. Some measure of the reliability and responsibility may be gauged from the disclaimer at the start of the document:

Disclaimer

The views expressed in this publication are those of the authors and not necessarily those of the Australian Agency for International Development (AusAID).

But the names of the authors are not provided.

As you can see, apart from a low in the early records, which seem to be associated with a tropical cyclone, there seems to be no great change in sea level since the early 1990s.

Explaining it away

Vincent Gray explained in his newsletter, NZCLIMATE AND ENVIRO TRUTH NO 181 13th August 2008, that something had to be done to maintain rising sea level alarm, and it was done by in a paper by John R Hunter.

Hunter first applies a linear regression to the chart for Tuvalu. He gets -1.0±13.7mm/yr so Tuvalu is actually rising! The inaccuracy is entirely due to the ENSO (El Ni–o-Southern Oscillation) effect at the beginning. He then tries to incorporate old measurements made with inferior equipment and attempts to correct for positioning errors. He gets a "cautious" estimate for Tuvalu of 0.8±1.9mm/yr. He then tries to remove ENSO to his own satisfaction, and now his "less cautious" estimate is 1.2 ± 0.8mm/yr.

Does this show the island is rising? Just look at the inaccuracy. The commonsense interpretation of the sea level graphs is surely that Tuvalu, and 11 other Pacific Islands, are not sinking over the time span concerned. The sea level is virtually constant.

Similar manipulation of sea level data is described in Church and others (2006), who consider the tropical Pacific and Indian Ocean islands. Their best estimate for sea level rise at Tuvalu is 2 ± 1 mm/yr from 1950-2001. They wrote "The analysis clearly indicates that sea-level in this region is rising." Does this square with simple observation of the data in Figure 15? They further comment: "We expect that the continued and increasing rate of sea-level rise and any resulting increase in the frequency or intensity of extreme-sea-level events will cause serious problems for the inhabitants of some of these islands during the 21st century." The data in Figure 15 simply do not support this excessive alarmism.

Models and ground truth

Before getting on to the next part of the story I shall digress on to the topic of "models" versus "ground truth". The past twenty years might be seen as the time of the models. Computers abounded, and it was all too easy to make a mathematical model, pump in some numbers, and see what the model predicted. It became evident very early that the models depended on the data that was fed in, and we all know the phrase "Garbage in, Garbage out". But the models themselves do not get the scrutiny they should. Models are invariably simplifications of the natural world, and it is all too easy to leave out vital factors.

"Ground Truth" is what emerges when the actual situation in a place at the present time, regardless of theories or models. It is a factual base that may help to distinguish between different models that predict different outcomes---just what did happen, and what can we see today?

In the case of Tuvalu's alleged drowning, we are usually presented with a simple model of a static island and a rising sea level. As Webb and Knetch expressed it: "Typically, these studies treat islands as static landforms". "However, such approaches have not incorporated a full appreciation of the contemporary morphodynamics of landforms nor considered the style and magnitude of changes that may be expected in the future. Reef islands are dynamic landforms that are able to reorganise their sediment reservoir in response to changing boundary conditions (wind, waves and sea-level)".

In simple language we have to include coral growth, erosion, transport and deposition of sediment and many other aspects of coral island evolution. The very fact that we have so many coral islands in the world, despite a rise in sea level of over 100 m since the last ice age, shows that coral islands are resilient---they don't drown easily.

The actual growth of islands in the past twenty years

Webb and Kench studied the changes in plan of 27 atoll islands located in the central Pacific.

They found that the total change in area of reef islands (aggregated for all islands in the study) is an increase in land area of 63 hectares representing 7% of the total land area of all islands studied. The majority of islands appear to have either remained stable or increased in area (86%).

Forty-three per cent of islands have remained relatively stable (< ±3% change) over the period of analysis. A further 43% of islands (12 in total) have increased in area by more than 3%.

The remaining 15% of islands underwent net reduction in island area of more than 3%.

Of the islands that show a net increase in island area six have increased by more than 10% of their original area. Three of these islands were in Funafuti; Funamanu increased by 28.2%, Falefatu 13.3% and Paava Island by 10%. The Funafuti islands exhibited differing physical adjustments over the 19 years of analysis. Six of the islands have undergone little change in area (< ± 3%). Seven islands have increased in area by more than 3%. Maximum increases have occurred on Funamanu (28.2%), Falefatu (13.3%) and Paava (10.1%). In contrast, four islands decreased in area by more than 3%.

Conclusion

In summary Webb and Kench found island area has remained largely stable or increased over the timeframe of their study, and one of the largest increases was the 28.3% on one of the islands of Tuvalu. This destroys the argument that the islands are drowning.

Vincent Gray, an IPCC reviewer from the start, has written SOUTH PACIFIC SEA LEVEL: A REASSESSMENT, which can be seen here:

http://scienceandpublicpolicy.org/south_pacific.html.

For Tuvalu he comments that "If the depression of the 1998 cyclone is ignored there was no change in sea level at Tuvalu between 1994 and 2008; 14 years. The claim of a trend of + 6.0 mm/yr is without any justification".

References

Church, J.A., White, N.J. and Hunter, J.R., 2006. Sea-level rise at tropical Pacific and Indian Ocean islands. Global and Planetary Change, v. 53, p. 155-168.

Webb, A. P., Kench, P. S. 2010. The dynamic response of reef islands to sea level rise: evidence from multi-decadal analysis of island change in the central pacific, Global and Planetary Change, v. 72, p. 234-246.

Emeritus Professor Cliff Ollier is a geologist and geomorphologists. He is the author of ten books and over 300 scientific papers. He has worked in many universities including ANU and the University of the South Pacific, and has lectured at over 100 different universities.

|

|

Lavoisier the Man

Bio and Image |

|

|

Click above for latest SOHO sunspot images.

Click here for David Archibald on solar cycles. |

|

|

Where is that pesky greenhouse signature?

Click here for David Evans's article. |

|